UK TEAM unveils PRETTY FRIGGIN’ DETAILED PLAN to send HUMANS TO MARS

Perhaps fittingly, the Imperial College of London has unveiled a detailed-as-fuck plan to send humans to Mars.

Scientists from the Imperial College of London have outlined an incredibly ambitious concept mission to land astronauts on Mars. It’s hoped that the plan will spark further debate about the feasibility of sending humans to the Red Planet in the near future.

The plan, which was developed in conjunction with the BBC, is certainly well thought out.

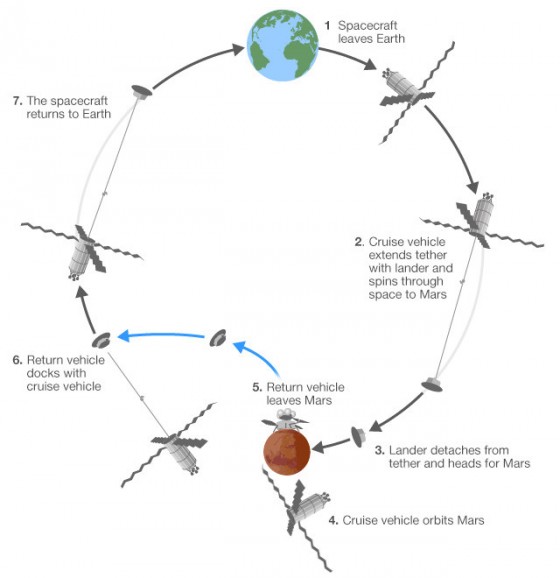

It would see a three-person crew journey to Mars in a spacecraft that generates artificial gravity (to prevent loss of bone density) and a magnetosphere (a kind of ‘deflector shield’ to protect astronauts from harmful radiation).

As for the magnetosphere, it would be generated by superconducting magnets.

The team also designed a two-part spacecraft consisting of a lander equipped with a heat shield.

Once at Mars, the two vehicles would contract together. The astronauts would pass into the lander for their detachment and descent. Multiple parachutes would deploy to slow the craft, followed by thrusters used to slow and guide it to the landing site.

But getting back home will be much more complicated. The BBC explains:

The return vehicle would land at a latitude where water ice would be found in large amounts just a few centimetres beneath the surface. Robotic devices would mine the ice, which would then be split into hydrogen and oxygen using electrolysis.

These gases could be used as fuels on their own, or the hydrogen could be combined with carbon dioxide from the Martian atmosphere using a catalyst to produce methane, which is a more stable and energy-dense fuel than hydrogen.

The team suggest we could mine Mars for ice to fuel the return craft As the Imperial team propose landing near the equator, a crew would have to travel by rover to a cooler latitude where the return vehicle and ice-mining devices would be waiting. Several hundreds of kilometres may have to be crossed, posing both risks and opportunities to further explore the Martian landscape.

Should they make it safely, the crew would have a narrow launch window to ensure the quickest most fuel-efficient return to Earth.

After leaving Mars, the return vehicle would dock with the orbiting cruise vehicle and replace the Martian lander as the counter-balance within the spinning tethered structure en route to Earth. Like the lander, the return vehicle would have to be fitted with a shield to protect the crew during extreme solar activity.

After nine months, the capsule would reach Earth and dock with the ISS — home sweet home.

TL;DR? It’s detailed.