First Commercial Asteroid Mining could start in Three Years; get me to Ceres Station!

Man, I don’t know if I believe the Hype, here. Asteroid mining in three years? Cities in space in thirty years? But, oh, do I want to. Do I ever want to.

If Deep Space Industries has its way, there’ll be a small robotic lander on a nearby asteroid in just three years. That’s the latest phase of the California-based asteroid mining company’s plan to bring about an outer space real estate boom by creating a resource supply chain off Earth.

“Our thirty year goal is to build cities in space,” Deep Space Industries CEO Daniel Faber told Gizmodo. “You need a lot of raw materials from asteroids to enable that.”

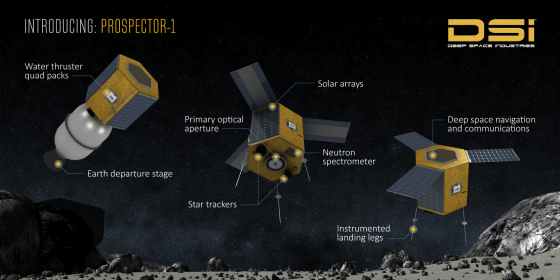

Asteroid mining is still in its infancy—no would-be miners have managed to land on a space rock, much less harvest the water and metals locked away inside of it. But if a spate of recent announcements are any indicator, Deep Space Industries is hoping to lead the charge. Earlier this year, the company unveiled Prospector X, a tiny robotic spacecraft that’ll sit in low Earth orbit testing technologies for future asteroid prospecting missions, including water-powered propulsion and optical navigation systems. That spacecraft is on track to launch in late 2017.

Shortly thereafter, the company intends to ship off the very first asteroid-bound Prospector 1. This vehicle—just 50 kilograms when fueled up—will hitch a ride into low Earth orbit before pointing itself at a target, firing up the water-powered thrusters, and setting sail for riches and glory.

“Our thirty year goal is to build cities in space. You need a lot of raw materials from asteroids to enable that.”

“We’ll begin to survey [the asteroid] from a long way away, getting an idea of the shape,” Faber said. “As we move closer and get higher quality spectral data, we’ll start to understand where on the surface are the best places to find resources.”“In the last phase, we have to touch the surface of the asteroid,” he continued. “We need to understand the properties of the rocks—how hard they’re going to be to mine.”

Landing on an asteroid also allows Deep Space Industries to lay claim to its resources—sort of. While no company, government or individual can own a celestial body under the 1967 Outer Space Treaty, in principle, companies shouldn’t interfere with each others’ space-based activities, Faber said.

We’ll see how that plays out. There could be a several year gap between the arrival of the first Prospector 1s and the first actual mining gear— a harvesting spacecraft that will tug the asteroid to a processing facility. If a competitor meanwhile decides it wants to harvest the exact same rock, things could get very interesting.

Artist’s concept of a harvester spacecraft, which will tug a promising asteroid to a space-based processing facility. Image: Deep Space Industries

One new piece of legislation that clearly works in Deep Space Industries’ favor is the US Commercial Space Launch Competitiveness Act, which grants companies legal ownership over any resources they’re able to mine in space. In other words, if you harvest it, it’s yours.Deep Space Industries hasn’t chosen a target for its first prospecting mission. “We have a list of targets, but we haven’t picked a specific one yet,” Faber said. “We’d like to send prospectors to a bunch of them.”

The ideal space rock will be rich in water, which can be used to make rocket fuel, volatiles like CO2 and methane, and useful metals. As Deep Space Industries told me several months back, the point is not to sell these resources back on Earth, but to create a space-based supply chain so that others can start building in and beyond orbit at a lower price point. It currently costs thousands of dollars to send a kilo of material into space, vastly restricting what can be done up there.

For instance if you want to build cities, you’re going to need much more air, metal, and water than can affordably be shipped from the ground—even with Elon Musk’s reusable rockets. “All of the high tech stuff, like computers, won’t be made in space for a long time,” Faber said. “Our goal is to complement that.”