Astronomers have taken first picture of planet orbiting a star. Spaceswoon++

Woo! I’m totally excited about us doing as a civilization something I probably thought we had already done! Astronomers have taken their first picture of a planet orbiting a star, allowing us to plan our travel to this planet. We can go there, right? We got this, correct? Pack your bags, it’s on!

Bad Astronomy:

Today astronomers announced a new addition to a very exclusive club: an actual, direct picture of a planet orbiting another star!

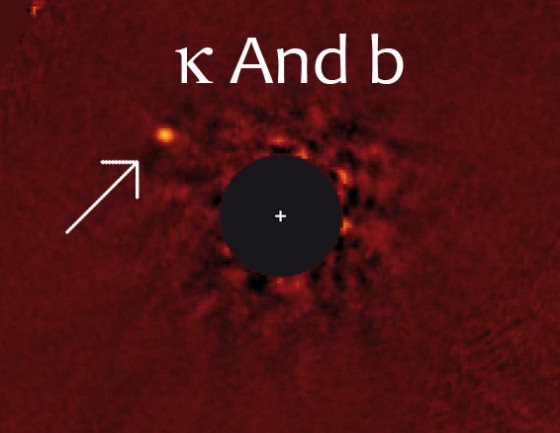

The newly discovered planet is called Kappa Andromedae b, or κ And b for short. I’ll tell you all about it, and why it’s so very interesting, but first, here’s the picture:

The star, κ And, is bright enough to see with the naked eye. It’s about 170 light years away, pretty close as these things go (a mere 1700 trillion kilometers; better pack a lunch if you plan to visit). It’s more than twice the mass of the Sun, much more luminous, and pretty young: about 30 million years old. Our Sun is 4.6 billion years old, for comparison. κ And is the most massive star yet seen to harbor a planet.

The astronomers used the Japanese Subaru telescope in Hawaii to specifically target nearby stars, hoping to see either planets or, more likely, disks of material surrounding the stars from which planets form. Those disks are easier to spot (they’re bigger and brighter) but finding a planet is a pretty awesome bonus.

κ And b, the planet, was first seen in images taken on Jan. 1, 2012—what a way to ring in the new year!—using a telescopic observing technique that makes most of the light from the star go away but leaves the planet’s light to get through. If you’re curious you can read about the method, so I won’t go into details. But I will say I used a similar technique to look for planets and disks around nearby stars back when I worked on Hubble, and it’s nice to see it working so well now.

More than 800 planets are known to orbit other stars, but the methods used to find the vast majority of them are indirect: We see their effect on their stars, but we don’t see the planets themselves. Using various methods, fewer than a dozen exoplanets have been actually spotted in pictures like this one with κ And b, so it’s a pretty elite membership. We’re on the verge of technology—space telescopes, better hardware on the ground, more clever software techniques—that will open the floodgates of finding these elusive and dim worlds, but for now each one we find is a precious jewel.