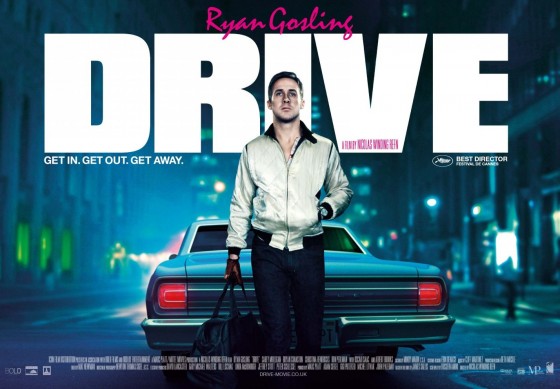

Drive: Life Outside the Five Is Well Worth It

(Warning: This review contains some minor spoilers.)

(Warning: This review contains some minor spoilers.)

Five minutes. That’s all the Driver (Ryan Gosling) gives his fellow criminals on a heist. No more, no less. Anything before or after that allotted time is not his concern; it is outside his frame of reference. But within those five minutes, he is all in, willing to do anything to get the job done. Because, during those five minutes, he is doing what he was meant to do, doing what defines him: He is behind the wheel of a get-away car, driving relentlessly for a few minutes at a time.

This resolute stipulation by the Driver opens and structures Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, a film that ends up being a skillful exercise in fashioning a distinct boundary in a stripped-down story until it can no longer be held, until life creeps in and violence eventually bursts out. And the story’s compelling interplay between actions, both consequential and minute, in and outside the Driver’s all-or-nothing five-minute philosophy, is what elevates the rather customary plot to impressive heights.

The Driver drives part-time; that is, time that is dashed with some sense of uncertainty and danger, an avenue to an exciting existence, even though the Driver manages to make it look easy. By day, he does stunt work for movies, providing daring car chases and crashes for the big screen. By night, he is the driver for heists, providing the compulsory exit strategy for big scores. Between these two professions, he lives alone, with few complications or flourishes; yet his entire life is nevertheless stimulated by driving. On his downtime, he unwinds by going for joyrides (if not overly joyous on the surface) and fixes car parts in his unfurnished apartment, a particularly effective mise-en-scene and metaphor for his life impelled by nothing but cars. His driving gives his life some semblance of meaning or, at the very least, it gives him something to do (and very little else).

And it is fitting that cars end up leading the Driver outside of his comfort zone. After having remained silent and aloof to his next-door neighbor Irene (Carey Mulligan) in an elevator and avoiding her and her young son Benicio in the local grocery store, the Driver is finally drawn to her when she has car problems in the store parking lot. This small intersection propels the story forward, taking the Driver outside of his shell, as he quickly becomes a potential love interest and protector. The Driver finds himself at an existential crossroad, where his self-imposed exile from real human interaction comes under fire. And by having something more substantial in his everyday life, he finds an actual impetus for driving–for living beyond the momentary and the solitary. He can take Irene and Benicio on a ride along the L.A. River or take Irene for a spin at night. Simply, the Driver can take them where they need to go, and it is all because he is willing to drive them.

But when Irene’s husband Standard (Oscar Isaac) gets released from prison and swiftly finds himself mixed up with thugs, the Driver, now invested in the safety of the family, opts to help Standard by driving in a heist he is forced to do in order to obtain his freedom. And from here, as the saying goes, all hell breaks loose–mostly breaking loose from the once reserved Driver, who reveals himself to be a stone-cold killer when he gives himself over to his more violent impulses. His boundary between life within and without the get-away car is no longer fixed; invigorated by a passion for Irene, Benecio, and perhaps even Standard, the Driver is willing to go all-out for them in their service. And it takes a lot more than just five minutes to try to get the job done.

This transition from the Driver’s five-minute/part-time limitation into a full-time, all-consuming profession creates a fascinating tension throughout the film and opens up the way for terrific bursts of energy. Calling the Driver a man of action (or inaction) is a misnomer; he is man of inertia until external forces get in his way. Then, his coiled-up manner gives way to uninhibited pulverization of those forces that endanger Irene’s family. And the film’s portrayal of violence brilliantly mirrors this rapid-forming intensity in its main character. Subdued and humane moments incite flashes of concentrated brutality, and Refn relishes the opportunities to take these brief instances and make them shocking and shockingly beautiful. Any austerity, in character and in the narrative, is ruptured by bullets, smashed by hammers and heels, and sliced beyond all recognition. This is a dynamic motion picture, and it stems from its abrupt movement from reservations to excesses, from silences to dissonances (and a blasting synth-heavy soundtrack, no less), from tender offerings of smiles and knowing stares to loved ones to letting more aggressive actions do all the talking in what culminates in a showdown of shadows. From beginning to end, Drive shows the ins-and-outs of exhilarating filmmaking just as it shows real driving: It’s not merely the speed that makes for an interesting journey; it’s the punctuation of stopping and going in tandem with the winding and full-throttling that makes it all work–and all of these intricacies depend on who’s in the driver’s seat.

Just like the Driver’s five-minute provision, Refn has allotted time for his mythic hero; he makes sure that the Driver has little to nothing before or after what is presented in the film. Most of his past remains unknown, and his future is ambiguous. But in the time that is given to the audience, the experience is certainly rewarding. During the course of its running time, Drive ultimately holds nothing back in its pursuit to take the audience for a ride, and those who go along make off like bandits.