Hypertext: A Garden of Forking Clicks.

(I originally wrote this as a blog post for an educational class I’m taking in grad school. A lot of the references make sense only in context of the class, but if you’re bored here’s 1,700 words of me theorizing about our culture in my usual nonsensical way.)

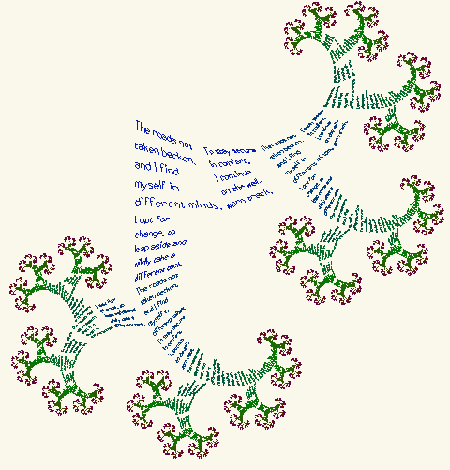

The fact that you’re reading this on the internet, specifically on a blog, means that digital writing has won. The fact that you’ve clicked links, traversed what Jay Bolter calls “hot” text in Writing Space: Computers, Hypertext and the Remediation of Print is more than enough proof of the New World Order. I knew this before I read chapter 3 of his book. A book published in 2001, which means in the world of hypertext and the digital age that is far past being a dinosaur and quickly approaching petroleum. That’s why I signed up for this chapter, why I ventured to blather about it on the internet and in the classroom. I’m a believer. In fact what I found in Bolter’s book wasn’t sage-like insight or futurism, it was an adorable relic of the past. For while there is no doubt that hypertext is involved with the remediation of print, I would argue that hypertext is actually the remediation of text, or more specifically the possibilities of it. So what I’m proposing through these words, translated into bits and bytes, translated into a Blogger document, translated into meaning via your eyes and into your brain is that what Bolter predicted was the paradigm shift in print text, and what it has been swept up in is the hypertextual shift in our own collective consciousness. And since we’re dutiful teachers and future teachers, the question should become how do we use this?, since as I’ve already indicated it’s too late to try and fight it.

Read these words on your computer. It’s already won.

Bolter and the Remediation of Print.

Chapter Three of Bolter’s book is concerned with the remediation of print in the world of hypertext. As I’ve already lamented, the chapter itself is part of a relic from an age where the iPad wasn’t dreamt of, and the Kindle wasn’t giving book dealers anxiety attacks. So it’s hard to take it entirely seriously, but it does make some good points, though it never seems to take that next daring step and predict what it all means. Perhaps that’s coming in a later chapter. A good portion of the chapter is spent trying to serve as a mediator between two warring factions: the Luddites who swear off the notion of digital writing. Imagine them, if you will. Phone jack ripped out of the wall, chests heaving swearing at their Compaq laptop from 1998. On the other hand are the techno fetishests who even back in 2001 were worshiping their copy of Neuromancer and proclaiming something like the “cumbersome nature of the flesh.”

I would know, I’m one of them.

Anyways.

The gist behind Bolter’s chapter is that digital writing and hypertext is not some new creation walking onto the scene. Shiny, fancy, new. Instead Bolter ties it into his narrative of the remediation of print going on throughout the centuries. In his words, electronic writing with its multiple forms of representation is actually reminiscent of hieroglyphics because the computer “welcomes elements that we in the West have long come to regard as inappropriate to writing; it constitutes…a continuum in which many systems of representation can happily coexist” (37). Fair enough. Remediation is essential not only to the point of the chapter, but also the book. So Bolter is pushing hard. Can you hear him laboriously grunting in an effort to corroborate his thesis?

For what it’s worth, I buy into what he’s selling. Nothing new under the sun! No sir. What Bolter wants to argue is that the “newness” of digital text is predicated on how it differs from that which it pays homage to. Digital writing can only be a new form of writing by simultaneously paying homage to the older forms that it is breaking out from. So while it sloughs off the printed page, it also reflects that page and also goes beyond it. Under this conceit digital writing strikes me as the kid who goes off to college and totally acts up, but only because Daddy and Mommy are footing the bill. It may not be the most accurate depiction but it’s late and it’s making me laugh while I labor under my own efforts.

Hypertext(ual): What It Means, Where We’re Going.

The sexier segments of Bolter’s chapter are those in which he begins to dip his toe into theoretical water. I was disappointed that he spent more time defending the middle ground between print and digital and less time asking what does this all mean? Digital writing is becoming prominent, hypertext is vomiting up all over the place whether the scholars and fogies want it to. So what does this mean? Bolter briefly begins to address this when he comments that “some supporters of hypertext may even argue that hypertext reflects the nature of the human mind itself — that because we think associatively and not linearly hypertext allows us to write as we think” (42). Yes Bolter!, I proclaimed. Tell me more. Where do you think this will take us? Being freed to dabble in a world that more accurately reflects our consciousness? The slipstream of our thought process. That’s where he stops though, daring not to ask where we’re going (again within this chapter) but rather simply that hypertext is the remediation of print.

However! Hypertext isn’t merely the remediation of print. As we’ve discussed in class, text itself is much more than words on a page. A variety of things can be looked at as text: books, movies, advertisements, pictures, posters, television shows. Only willing and waiting to be read. Another trope we’ve discussed in class. Hypertext is more than a way of looking at a print, or digital writing. Instead it’s a concept that has writhed its way into our collective psyche, being reflected in much more than the way we write. We are living in a hypertextual world where reference is everything, where non-linearity is king. A time that may be staggering to someone from even a hundred years ago.

Consider the short stories that we had to read this week. Michael Joyce’s Twelve Blue and afternoon.They hop, skip, and jump around the page. Frankly, I think they’re unsatisfying and gimmicky and not in the same way that led me to build and altar to Mark Z. Danielewski. They’re effect in demonstrating hypertextual storytelling. In digital print. If you’re me, you blindly clicked around a couple of times, felt unsatisfied, and left. What I want to push is the idea that this sort of non-linear narrative has bled its way into other avenues of text. I can think of no bigger example of the pop-culture take over by hypertext than that Frankenstein’s Monster that JJ Abrams, Damon Lindelof and Carlton Cuse gave birth to.

Everybody is LOST In Hypertext.

LOST isn’t just the source of the greatest let down in recent television history. It is also a testament to both the power and the pitfalls of hypertextuality. It began with simple non-linear narratives interspersed through the main storyline. One simple click of the “hot” story text to someone’s flashback and then they returned. As the show continued it sprawled out. Further and further into the madness of hyper referentiality. Those wooshes took the viewers not just into a character’s past. It took the viewers into the past, and into the future, and into different dimensions. The show was hypertext at its finest. Unfortunately it was hypertext at its worst, as the show became an untenable mess. By the end of the series the writers were lost in their own sea of diversions, gobbled up a pantheon of questions never answered. Bolter describes hypertext as being “extremely malleable” and it “can be fashioned into one tree or a forest of hierarchical trees” (32). Unfortunately for the writers, they built themselves a labyrinth they could never escape from.

Man, it sucked.

The point is that hypertext has far exceeded being merely a question of print living or dying. It’s a concept we live and breathe. It’s spread to movies. It’s spread to music. Genre-smashing artists such as Between the Buried & Me start off annihilating ear drums only to segue into a western dance-off in Ants of the Sky. (If you’re meek, it’s around eleven minutes in.) It seems at this point that hypertext has won. Or if you’re not a sadly testosterone soaked male and you don’t need to measure everything in terms of wins and losses: it’s here, it’s arrived.

As teachers, now what?

Pedagogy In The Era of Forking Paths.

All of these forking paths in my diatribe converge if momentarily on this important fact: we’re all aspiring teachers and professors here. So the salient question is: what does preparing to teach the Children of the Hypertext (not to be confused with the Children of the Atom) mean? The students we inherit will be used to a world where everything forks and diverges at almost imperceptible speeds. How much thought goes into clicking that link? It’s pointless to consider this mutation good or bad, but rather all our energy should be directed towards figuring out how we can harness hypertext for our benefit. Dry texts by old dead white guys may be important to us, and they can be important to our students. The question becomes how we convey this importance.

It makes sense to me to begin to bring the hypertext into the classroom, our own class functioning within the same mechanisms as the internet and our developing world. An introduction to Macbeth could be a student reading aloud the opening scene. Whoosh! Click! Then we’re onto watching a video of a performance of the opening scene. Whoosh! Click! Now we’re back to a classroom discussion regarding this scene. If nothing else, hypertextual existence should demand dynamism out of the classroom. Static presentations and top-down instruction were never the most fun. Don’t let your Mom and Dad wax nostalgic about the “good old days”, I’m sure they were bored as Hell too. They’re certainly not fun in the world of instant gratification. At its core, hypertext is dynamic, and our pedagogy should reflect a desire to meet these dynamic expectations of our students.

Things To Consider:

– Do you believe that hypertext is merely the remediation of print? Is it possible for new modes of writing to not bare vestiges of the old?

– For that matter, do you view hypertextuality as anything more than gimmick?

– Who is faster, Batman or Superman?

– Is there room for old, longer texts in a world of constant diversion and fragmenting attention? How do you teach them?

– How do you approach classroom dynamics in the age of the immediate and hypertext?